The following is an article by Tim Cooper from this morning’s Chartered Institute for Securities and Investment (CISI) Review magazine. It is aimed at Financial Planners, but it is quite accessible and I think you will find it interesting. I have highlighted a couple of particularly important sentences.

“October … is one of the peculiarly dangerous months to speculate in stocks,” says the title character in Mark Twain’s 1894 novel Pudd’nhead Wilson. “The others are July, January, September, April, November, May, March, June, December, August and February.”

The ‘October effect’ – psychological anticipation that financial declines and stock market crashes are more likely to occur during this month than any other – has its origins in the Panic of 1907, which started in mid-October and saw the New York Stock Exchange fall almost 50%. Then in 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) fell by a combined 25% on 28 and 29 October, triggering the Great Depression, and on Black Monday on 19 October 1987, the DJIA fell by 22.6%.

“Humans have a psychological tendency to see patterns, even if they’re not statistically robust, leading to sub-optimal decisions”. And, although the first ripples of the global financial crisis began with problems in the US subprime mortgage market spreading to Europe in the summer of 2007, the crisis was officially recognised as such when G7 leaders held an emergency meeting in Washington DC on 10 October 2008.

But crashes can and do happen in any month. Black Friday 1869, which saw the collapse of the US gold market, and Black Wednesday 1992, when a collapse in the pound forced Britain to withdraw from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, both took place in September. The dot-com bubble burst in March 2000, and, most recently, the 2020 Covid crash started in February.

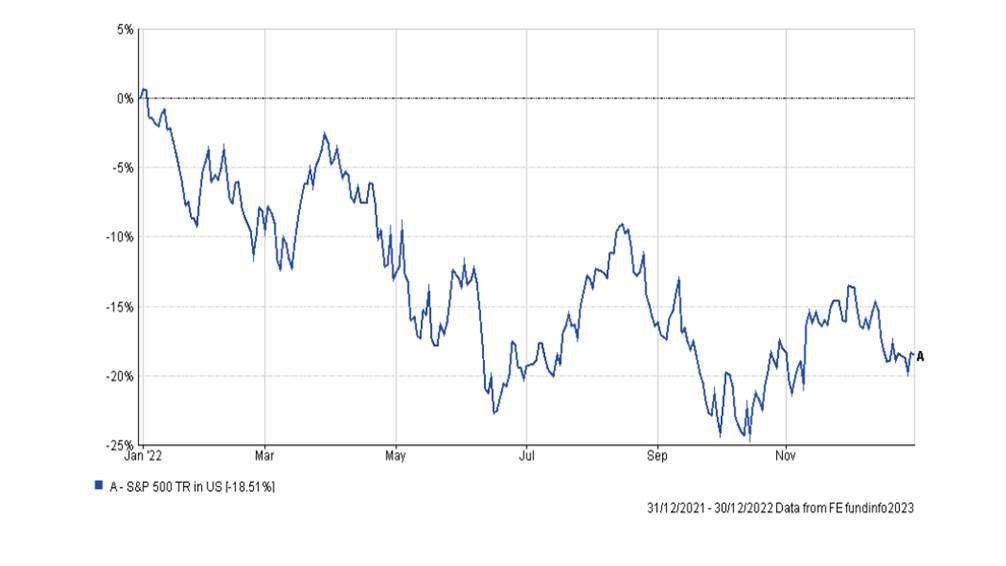

However, October endured a 35% higher standard deviation (volatility) of monthly returns than the average for the other 11 months of the year, according to an August 2023 CFRA report shared with the CISI. So, what’s behind the stock market movements the month has historically experienced?

Possible causes

The psychological bias towards predicting a negative outcome for October could cause some investors to fear a downturn during the month, leading to emotionally biased decisions. Other theories focus on the uncertainty created by buildups to bi-yearly US elections, which start in November. There is also the fact that mutual funds’ (Unit Trusts in the UK) financial years end around 31 October, so they tend to trade more as this date approaches.

Another factor could be that trade volumes are naturally quiet during the northern hemisphere’s summer holidays, then gradually build to a peak in October. Russ Mould, Chartered MCSI, investment research director at online investment platform AJ Bell, believes this trend could be exacerbated by market psychology. He points out that investors tend to start the calendar year optimistically, but if third-quarter earnings, published in October, are disappointing, reality kicks in. Traders start closing positions, boosting volatility.

Whatever the reasons, these perceptions about October could create opportunities for investors. Contrarian investors, who trade against prevailing trends to exploit herd mentality, might short stocks – a hedging strategy that profits from any negative trend – during the month. Or they could buy volatility funds, which make money based on the degree to which prices change.

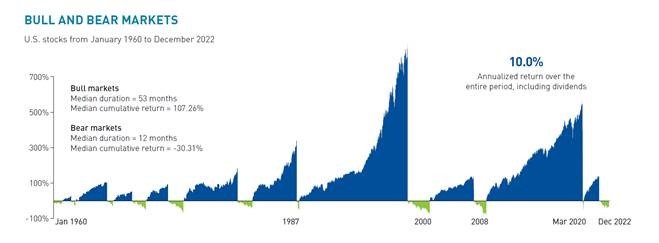

This volatility could also be attributed to opportunistic investors who de-risk their portfolios as October approaches by allocating towards lower-risk assets such as cash or government bonds. Then they might watch for a slump and increase allocation towards risk assets, such as equities. This strategy is supported by analysis by the Stock Trader's Almanac, showing that more bear markets have ended in October than begun. As a reminder a bear market (shares falling) ends when a bull market (shares rising) is about to begin. The timing of these events can only be measured with hindsight of course.

In the chart below, DJIA references the Dow Jones Industrial Average which represents just 30 stocks, the S&P 500, which covers 500 stocks and the NASDAQ, which is the index of tech shares only.

Another possible cause is that some traders may look for undervalued stocks in an autumnal slump, using fundamental analysis of share prices against financial performance. On the other hand, more pessimistic investors might simply stick to a defensive strategy and stay in lower-risk assets throughout the month.

However, any October-based strategy will rely on market timing, which many financial advisers (including me) avoid in favour of ‘time in the market’ – staying invested in risk assets such as shares – which they see as a more reliable long-term strategy.

“Traders might try to time money movements,” Russ says. “But I doubt advisers, clients or private investors will try to second-guess the October effect. Avoiding daily noise and taking a long-term view – with a target return, delineated risk appetite, and balanced, diversified portfolio – is the best plan."

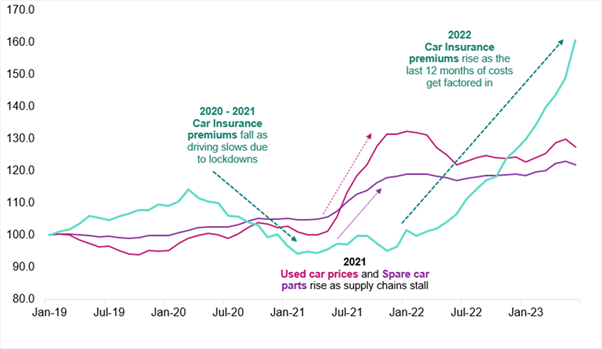

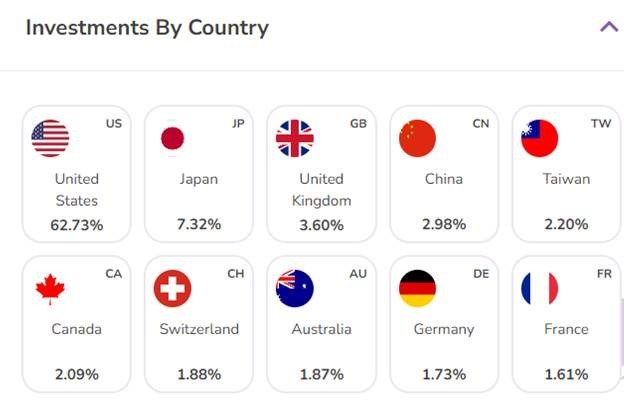

Though many have biases or opinions, no one knows for sure whether the current economic environment will result in inflation, stagflation, deflation, or just steady growth over the coming months, Russ says. And no one knows which sectors or assets will be winners or losers. Diversification across asset classes, geographies, sectors and styles will help smooth out any short-term volatility.

Automatic rebalancing, say once a year, will also help overcome any inclination to predict markets, he adds. All these factors combined help the portfolio defend against a range of possible macro and market outcomes, not just one.

‘Octoberphobia’ carries dangers, as it may lead investors to buy high, sell low, or waste time out of the market, which is one of the biggest genuine risks they face long term. By educating clients about psychological biases, advisers can help clients avoid such dangers.

Greg Davies, head of behavioural science at Oxford Risk – a behavioural finance fintech serving wealth managers, robo-advisers and pension providers – says advisers need to be particularly wary of such biases, as once investors have sold out of markets, it’s harder to get them back in again.

Greg points to a plethora of perceived seasonal trends, such as the ‘January effect’ (whereby stock prices purportedly rise in the first month of the year) and the ‘sell in May and come back on St Leger’s Day’ strategy (which warns investors to ditch UK shares before the summer months, and then buy them back in September, at the start of autumn).

Greg explains. “Individual investors also react differently based on their beliefs and perceptions. Advisers need to understand their clients' unique psychological profiles and tailor communication to help reframe the message.”

For example, some clients may have high composure during market crashes. Others may need more regular guidance and reassurance with personalised messages. Segmenting clients by such psychological dimensions enables personalisation that can help clients stick to their long-term plan, he says.

US-based Brenda Morris CFP®, founder of Humane Investing, agrees and says she avoids market timing in favour of “keeping it simple and sticking to the basics”. She encourages clients to keep their investments boring and get excitement elsewhere.

“I remind them of the case for diversification every year,” she says. “Also, dollar-cost-averaging (the smoothing benefit of regular saving) is a great way to hedge the volatility that is part of investing – in October as at any other time.” Having a financial plan to reflect on helps calm nerves when volatility would otherwise cause angst, she adds.

This article serves as a reminder that we should endeavour to resist our unconscious bias and ‘instincts’ around buying and selling investments, it’s impossible to time the markets routinely and consistently over the long-term and if we have a properly diversified portfolio, we don’t need to try.

I hope you have found this interesting but, if you have any questions about this piece or any other finance related matter, please do not hesitate to get in touch.

Yours sincerely,

Graham Ponting CFP Chartered MCSI

Managing Partner